CANAN ŞENOL ON TABOOS IN TURKEY

By Marie Büchert. Translated by the author from Danish. Original article at www.turbulens.net

Canan Şenol (b. 1970) belongs to a generation of young Turkish artists that express social commitment and a global outlook in their critical attitude to the Turkish societal system, and combine a subdued sense of humour with forceful provocation and aesthetic reflection. In her universe the naked body appears in indecent ways, dolls commit sexual assaults and torture victims describe the physical and psychological pains they have experienced. This article presents Şenol’s art based on three cultural taboos that are central to her: the power that religion, the family and the judicial system forces upon the individual.

THE DISCIPLINED HUMAN BEING

The limited latitude of the individual

Canan Şenol defines her art using a feminist slogan from the 1970s “private is political,” but she does not designate her work as feminist. She tells Turbulens.net that:

I consider myself a feminist, but when I describe my art, I don’t say that I do feminist art. I consider my art political.

Şenol claims that the slogan is of current interest because religious, family and political social structures considerably control and repress the free space of the individual. She is concerned that in general people from Turkey – and from other cultures too – deny the existence of these structures. In this way they tacitly accept that repression takes place and implicitly contribute to its maintenance. In her art, Şenol investigates the different structures and their effect on the individual with the artistic purpose of bringing about reflection.

What mostly provokes me comes from reality. Most of what we don’t want to see comes from reality. I want people to face reality.

Canan Şenol, Untitled, 2000, photography

The Panopticon as a model

Canan Şenol is inspired by the French philosopher Michel Foucault and his book on surveillance and punishment in which he develops the notion of present society as a disciplinary and normalising society in which everybody seeks to restrain themselves and live up to unstated expectations.

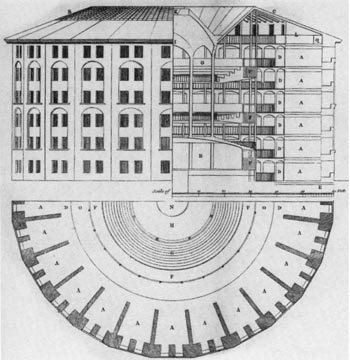

Foucault uses the panoptic building of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham as a symbol of the disciplinary and normalising society. Bentham describes the Panopticon as a circular prison with a room in the middle for the guard. The prison cells are oblong rooms that stretch from the centre of the building to its outer wall with only small strategically located windows. The inmates can neither see one another or the guard, whereas in contrast the guard has an unlimited view of the inmates. The inmates feel under constant surveillance and naturally behave as such: they discipline themselves and adapt their behaviour to what they believe the guard expects.

Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon, 1791, sketch. Published with permission from Wikipedia.org

Yet, the Panopticon is not only a prison but also a general model for other buildings in which a small number of people keep many more persons under surveillance with a minimal effort – hospitals, schools, military barracks etc. Foucault even claims that the Panopticon is an abstract model for all hierarchical structures in society. Accordingly, Şenol uses the Panopticon as a symbol to show how religion, the family and the state discipline the individual’s private life.

I think that all people believe that once in a while they live in a Panopticon. We are constantly influenced by others, by the state and the religion, and we often try to change our natural needs when we live with other people. We try to adapt our consciousness and become what other people expect from us.

When the individual becomes part of society, it is never free but always normalised in accordance with social conventions. In her art Şenol is concerned with cases in which the societal discipline and normalisation cause assaults on the individual’s integrity.

RELIGION’S CONTROL OF THE SEXUAL

Homosexuality before and now

In February 2006 Canan Şenol is exhibiting her work “Eyes Cannot Cognize” in Copenhagen. This piece deals, amongst others, with the way religious dogma intervene in private life and control the sexual behaviour of individuals.

“Eyes Cannot Cognize” is a large painting showing a homosexual couple having sex. The painting is placed in a glass exhibition case that Şenol has covered with a special green colour that has religious meaning in Islamic culture. The colour is usually used at ceremonies in the mosque. Şenol, therefore, expresses a powerful symbolic act when she uses the colour outside the sacred space – and a strongly provocative act when she combines the colour with an erotic phenomenon.

Homosexual relationships are completely natural, but some people don’t want to recognize their existence. They associate them with shame. In Turkey we always discuss whether or not there were homosexuals during the Ottoman period, but you can’t deny it. Homosexuality has always existed.

Today, homosexuality causes powerful emotions in Turkey, where Islam condemns its existence and where homosexuals usually hide from the public. At the same time, Turkish art history often reflects notions of homosexuality and Şenol deliberately uses the traditional mural as a source for “Eyes Cannot Cognize.” In her work she combines two completely different values of Turkish culture, an actual and a historic, and thereby relates a positive and a negative attitude towards homosexuality to one another. One might say that Şenol criticizes a suppressive dogma of Islam by placing it in a larger historical context.

The viewer is involved

In Canan Şenol’s opinion, religion disciplines the individual in a larger perspective too.

My point is not only related to the homosexuals, but also goes for private life to a considerable extent. This is the most important.

The green colour of “Eyes Cannot Cognize” covers the exhibition case so that it is impossible to see the painting inside the case at first. However, Şenol has made circular holes in the paint for the curious viewer to peep through. In that way, the face of the viewer replaces those of the homosexuals on the painting when peeping through the holes and similarly makes the viewer watch the intimate sexual situation when peeping through the opposite holes. The viewer can therefore choose between being under surveillance disciplining his or her own sex life, or instead surveying other people and controlling their sex life.

No matter which position, the viewer forms part of a power structure related to the Islamic taboo on homosexuality and sexuality in general. In both cases, the person puts his or her own private life under scrutiny and is forced to consider the power of religion – just as in real life.

PATTERN OF FAMILY ROLES

Stereotypical sex roles

Canan Şenol focuses on the private life of Turkish people in several other pieces of work. She often uses her physical body to underline the role patterns that individuals instinctively follow in family life.

The photographic series “Pain” (2000) shows Şenol naked and in the final stage of pregnancy, bent and screaming with labour pains, whereas the video “Fountain” (2000) highlights her plump breasts after labour. The video turns discussions on Duchamp’s famous urinal of the same name upside down: whereas the inanimate urinal only becomes a fountain by virtue of the male beam, Şenol’s breasts incessantly drips from milk and nourishment. According to Şenol, society brings up men to take on the outgoing role in life while it identifies women’s needs with her unborn children. Her pieces of work are powerful statements on the woman as a fertility goddess burdened with labour and breast-feeding.

Canan Şenol, Fountain, 2000, video

In our private lives we don’t always recognize what life we actually lead but rather tend to follow the social conventions without considering if they really ought to rule our lives. People who wish to have a family prepare for their roles as mothers and fathers: the women educate themselves to take responsibility for the household while men try to be strong and make money. If we didn’t think that way, we might be able to divide the roles differently.

Şenol places men and women at the same level in the disciplinary and normalising society and claims that its structures control the outgoing role of men as well as the withdrawn role of women.

Denied sexual and violent assaults

Canan Şenol thinks of widespread problems of abuse and violence in Turkish families as another taboo in Turkey.

It is uncommon to criticize the family and people don’t want to get involved with these problems if they are not affected personally. In principle they thereby justify the existence of domestic violence.

Şenol focuses on sexual assaults in cartoon-like narratives whose main roles are acted out by dolls with expressionless faces. For instance, one image shows a father abusing his under-aged daughter, while his son is watching secretly. Later on the son repeats his father’s act, raping his sister. Şenol believes that it is characteristic of Turkish culture that nobody discusses what happens in the home and that nobody interferes when other families have problems. However, in its own violent way the cartoon expresses that social problems are passed on to the next generation if we deny their existence.

In Şenol’s view we all reproduce the structures of society if we refrain from opposing them actively and consciously. Therefore she also holds women responsible for assaults which their husbands and sons commit in the home – just as she believes that neighbours and civil society in general have a responsibility.

BETWEEN JUDICIAL SYSTEM AND TORTURE

Violence and torture in the prisons

Another general theme in Canan Şenol’s art is the relationship between Turkish principles of law and the way the police and courts of justice enforce the law in practice. As a teenager, Şenol was picked up by the police twice at random and remanded in custody on no basis. In a number of her pieces of work today she is concerned with the conditions of inmates.

The Turkish society has a very good legislation which specifies that the police cannot act violently against people. Still, it is a reality that the police tortures inmates in the prisons.

“Transparent Police Station” (1998) deals with a group of students that was subjected to violent sexual, physical and psychological torture while in prison for having painted graffiti. It is a commentary prepared for the president of Turkey who in 1998 wanted to open the procedures of the country’s police stations to the public as part of a larger process of democratisation. Şenol in turn claims that the system is not democratic anyway, but rather that it is obvious and well known that those in power use violence against the citizens. In her view, there is no need to show the procedures of the police stations when the Turkish population already knows what happens inside.

Canan Şenol, Transparent Police Station (detail), 1998, installation

A corrupt judicial system

Canan Şenol thinks that corruption and torture are important sources of fear in Turkish society and that they contribute to the discipline and normalisation of the individual.

People are really afraid of the police and nobody dares accuse them of anything.

If criminals have the proper personal contacts, the judicial system acquits them rather than holding them responsible for their actions. Several concrete cases demonstrate that this concerns both prominent members of the mafia and leading businessmen, and soldiers and policemen.

In Şenol’s opinion the worst is that soldiers who participated in the military coup in1980 have never been put on trial. The soldiers murdered many civilians, yet, today they live an ordinary life. The Turkish population has to relate to them as they do to anybody else – smile in the street and exchange courtesies. In her art, Şenol questions whether this is possible at all: can a society develop positively if its population has no reason to trust the system and if its sense of justice is constantly neglected?

If somebody wrongly violates or distorts the law, we all have a responsibility for making them pay for it. That counts for soldiers or policemen too. The government and the people must point out that their actions are wrong and take responsibility for passing sentences, for the problems will continue if criminals are not pursued.

ART, LIBERTY AND CENSORSHIP

Even though her art often brings about powerful reactions, Canan Şenol does not believe that art in general has the force to remedy social problems.

I think of my art as a way of expressing ideas to other people, but I don’t think that I can change the world through my art. It is my way of being free, I only feel free in my art.

Paradoxically, Şenol uses her art to express thoughts and attitudes she does not feel able to articulate in her private life. As a citizen she is subordinated to the same norms and taboos as everybody else and restrains herself by adapting to the community. In her art she is freer and does not think about the consequences of a piece of work as much. Moreover, as an artist Şenol is able to communicate with far more people than she can as a private individual. And even though she takes over the taboos of religion, family life and judicial system in the Turkish context, the message to her viewers is evidently that the structural disciple and normalisation of the individual is a universal human problem.

I believe that these problems apply to the whole world, not only to my country. These things happen throughout the world.

In 2003, Şenol was picked up by the German police in the middle of the night when they subjected a solo exhibition of her work in Germany to censorship and shut the exhibition down because of complaints by people in the neighbourhood, even though this was against the law. The incident indicates that those in power control and discipline the individual outside of Turkey as well, and that the spotless self-concept that many western countries hold does not always correspond to the reality. In her art, Şenol draws our attention to the fact that we all have to contribute to solving these problems if we want the world to become a better place to live in the future.

Cph Kunsthal: www.kbhkunsthal.org

FACTS

Canan Şenol was born in Istanbul in 1970. She studied at the Business Administration Department of the Marmara University from 1987 to 1992 and continued her studies at the Painting Department of the same university from 1994 to 1998.

Şenol works with video, photography and installation among other things. Her works often deal with the boundaries between private life and society and highlights tabooed cultural phenomena with humour and power.

Şenol participated in the Istanbul Biennale 2005 and, besides Turkey, she has exhibited in countries such as Brazil, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. In the spring 2006, she is on a scholarship at The School of The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, USA.

In January 2006, Şenol visited Denmark for the first time. She held a workshop at the Royal Danish Academy of Art in Copenhagen and opened an exhibition of her work “Eyes Cannot Cognize” at the Cph Kunsthal. In this work, she discusses cultural phenomena such as sexuality, religion and the control of individuals and reflects on the problematic status of these phenomena in Turkey and societies throughout the world.

“Eyes Cannot Cognize” can be seen at the Cph Kunsthal, Vesterbrogade 6C (next to the Steno pharmacy and SAS Radisson), 1620 Copenhagen V until 23rd February 2006.